Cages

Beyond the Bars: 5 Surprising Realities of Designing for Big Cats

In the field of apex predator containment systems, we use the term "cat-a-tat" to describe a habitat designed to satisfy a predator’s every desire through natural foliage, platforms, and dens. Yet, as a conservation ethicist, I must acknowledge a sobering architectural truth: in the wild, these animals inhabit territories measured in square miles, not square feet. Even the most sophisticated enclosure is ultimately a jail cell for a species designed to roam. Designing these spaces requires a constant balance between the ethical necessity of space and the rigid engineering required to contain a 600-pound animal with the agility of a house cat "on speed."

The "Vacation Rotation" System

To combat the psychological stagnation of captivity, modern sanctuary design utilizes a "Vacation Rotation" system. This 2.5-acre enclosure serves as a massive common area connected to all roofed habitats via a complex network of tunnels and bridges. Each cat is rotated into this expansive space for approximately two weeks at a time, providing the "inspiration to be cats" that stationary enclosures cannot offer.

This rotational mindset addresses the biological needs of nocturnal, exceptional climbers who require movement and environmental change to thrive. By allowing cats to navigate through a maze of connected enclosures, architects simulate a sense of territory and agency.

No big cat belongs in a cage, but until we have better laws to protect exotic cats from being bred for lives of captivity and deprivation, we need to give them as much space and privacy as possible.

Engineering for Apex Predator Containment

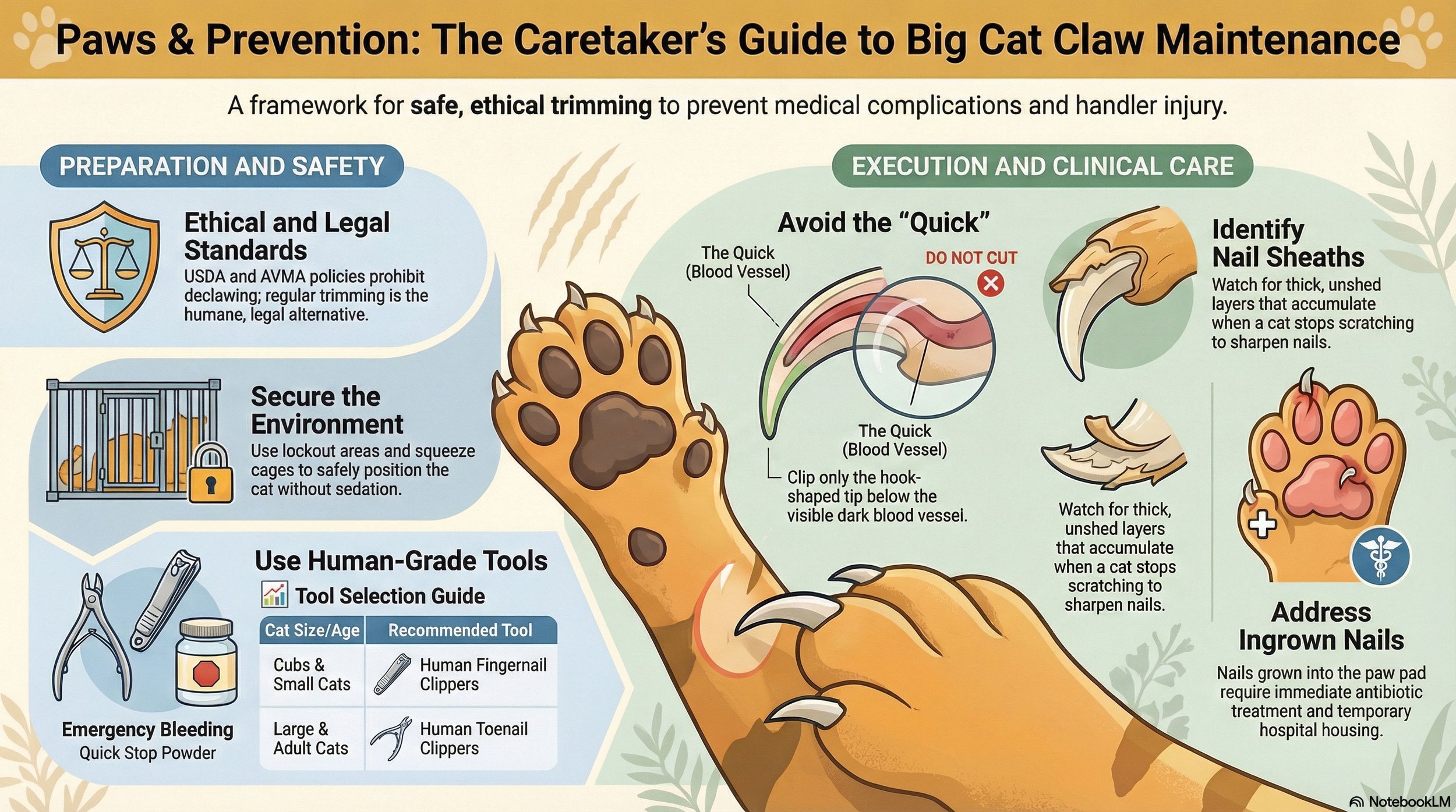

Structural standards for big cats have evolved from simple fencing to high-tensile engineering. Modern habitats utilize 5-gauge, double-galvanized 4x4 welded wire panels, an upgrade from the 6-gauge standard previously used. These panels are supported by 18-foot steel pipes sunk three feet into concrete, providing the stability needed to withstand the force of a predator with the weight of a small car.

Precision in hardware is the difference between a secure habitat and a lethal escape:

9-Gauge Hog Rings: Used to zigzag panels together; rings must only connect two rows of wire to maintain a high-tension grip.

Stake Wire: A specialized eight-inch footer with vertical points hammered into the ground and hog-ringed to the fence to fill gaps caused by uneven terrain and prevent digging.

Hog Ring Pliers and Fence Rippers: Professional-grade tools required for high-tension assembly and the safe deconstruction of wire walls during modifications.

The 16-Foot Clearance Rule: To prevent a cat from using a structure as a launching pad to bypass the five-foot overhang, all internal platforms and dens must be placed at least 16 feet from the top of the structure to the overhang.

The "Splash and Spray" Reality Check

The aesthetic of a sanctuary often clashes with the harsh biological reality of the inhabitants. Even when neutered or spayed, exotic cats spray "bucket loads" of urine daily, making indoor living impossible and requiring durable, non-porous outdoor materials. Furthermore, these animals are inherently destructive; water dishes must be elevated and pinned down with wire cages because the cats will otherwise destroy or relieve themselves in the drinking water.

From a landscaping perspective, a "Congo-styled lawn scape" with high, unmown grass is a functional architectural choice rather than neglect. This provides a vital visual screen and privacy barrier between solitary animals. While lush palmettos are often planted, they are frequently trampled "beyond recognition" within months by the sheer weight and activity of the cats.

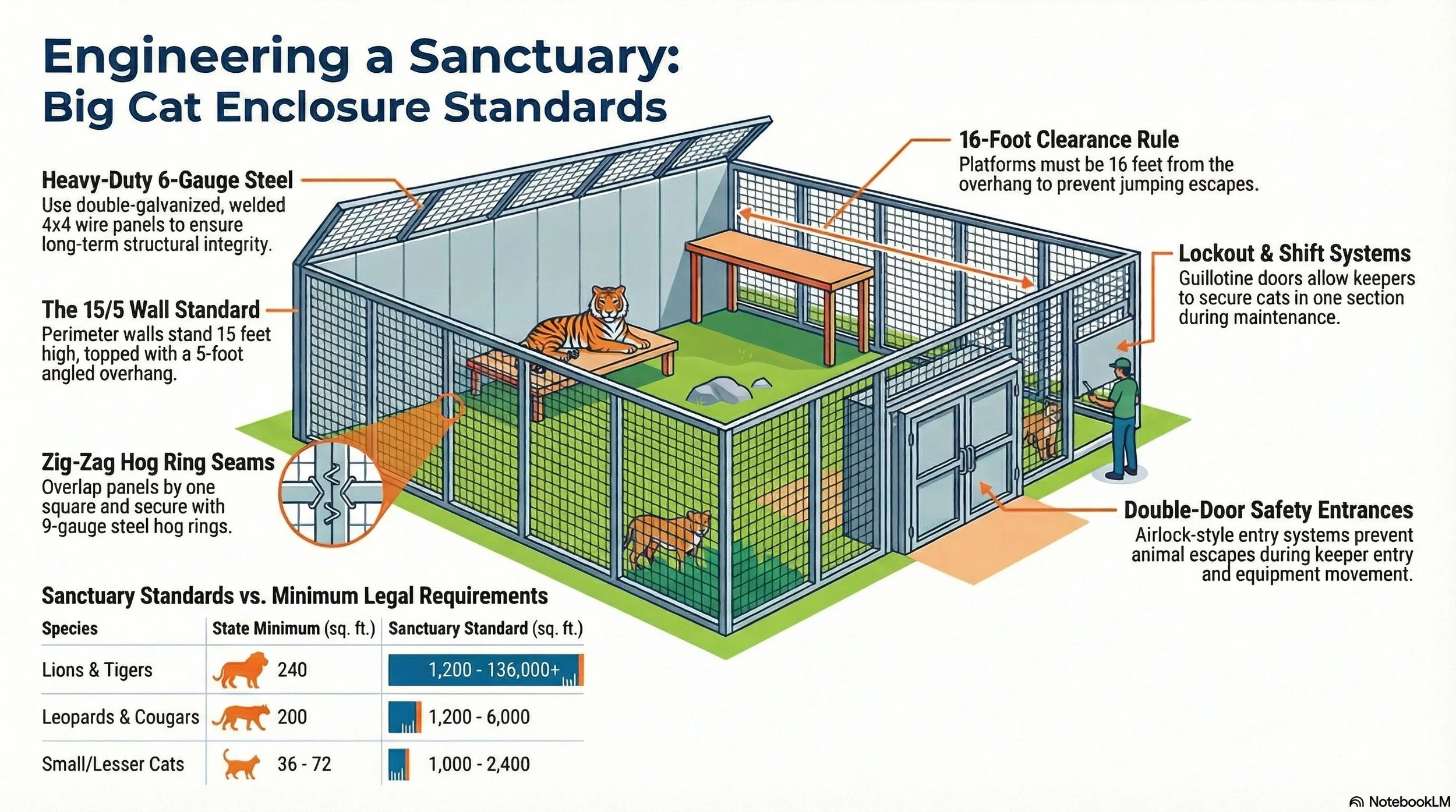

The Safety "Airlock" and The 30-MPH Rule

Safety protocols are built into the very footprint of the sanctuary through redundant, fail-safe systems. Every enclosure features a "safety entrance," or airlock, consisting of a double-door system where one door must be secured before the second is opened. These entrances are built large enough to accommodate heavy equipment, such as lifts for repairs or mowers, while ensuring the keeper and the cat remain separated.

Operational safety is also dictated by environmental variables and health monitoring:

The 30-MPH Rule: Because high winds can compromise open-air wire structures, cats are moved via guillotine doors into roofed sections whenever wind speeds exceed 30 miles per hour.

Feeding Lockouts: Keepers utilize small, secure sections of the habitat to place food and water, allowing maintenance to occur without a human ever occupying the same physical space as the animal.

Health Visibility: Dens are always oriented so the interior is visible from outside the enclosure, allowing keepers to monitor an animal’s health without the risk of entry.

The "Stand and Turn" Standard vs. Ethical Space

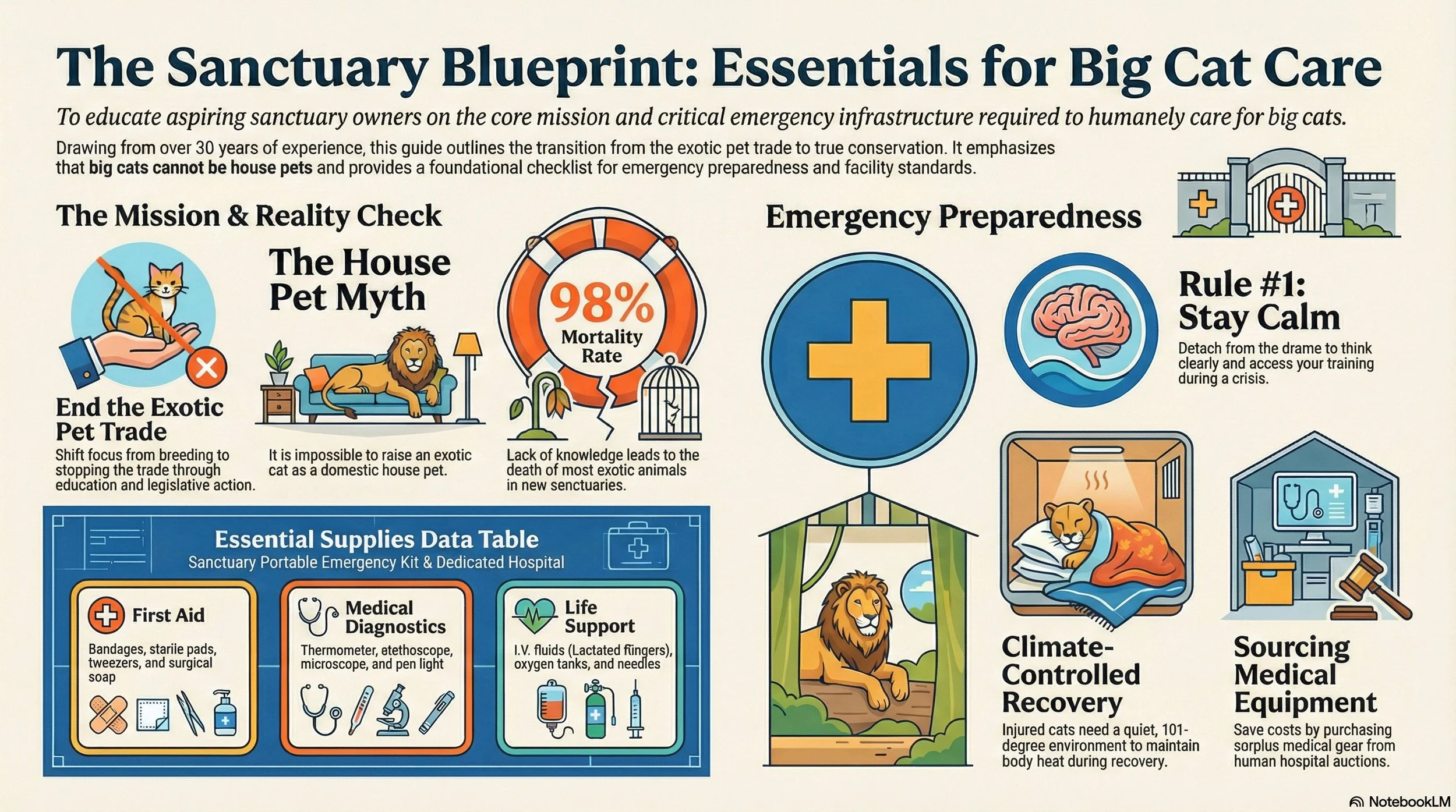

There is a staggering gap between legal requirements and ethical sanctuary design. The USDA and many state agencies only require that a cage be large enough for an animal to "stand up and turn around." In Florida, a 600-pound Siberian Tiger can legally be kept in a pen as small as 10 by 24 feet—a standard that is nothing short of cruel and inhumane.

While reputable sanctuaries provide habitats ranging from 1,200 to 136,000 square feet, the public often has a skewed perception of animal welfare based on high-budget zoo exhibits.

When you visit the zoo and see those magnificent million dollar enclosures, what you don't see are all the animals in tiny, off-exhibit cages. If animals must live in captivity, the least we can do is make them comfortable.

Conclusion: A Ponderable Future

The ultimate goal of sanctuary architecture is not just to build better cages, but to render them unnecessary. Through education and legislation, the mission is to end the exotic pet trade, making these specialized containment systems a relic of the past. Until that shift occurs, we must face a provocative ethical question: if we cannot provide the square miles these animals naturally inhabit, are we simply building better prisons, or is a "cat-a-tat" the best we can offer a species we’ve already failed?

All of the sanctuary cats have been relocated to newer, bigger cages at Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge as of Dec. 2023. The following described their cages at Big Cat Rescue prior to that move.

This video shows you how the cats easily navigate their mazes of connected enclosures and tunnels.

Here is another video showing the size of the smaller cats' cages and how the cats easily go through the doors from cage to cage. This is Zucari running through part of his suite of cages to catch up with the keeper with treats.

This video shows how our open-air enclosures are built. All open air enclosures have roofed sections attached in case of high winds.

Big Cat Enclosures

Here is where we get the only hog ring pliers that work: https://www.reddenmarine.com/pacific-mako-9000-wf-555-0-hog-ring-pliers.html

Below were the cage sizes at Big Cat Rescue. Our cats’ cages at TCWR are 5 to 20 times larger.

By Species State Requirements Our Cages

Lions and Tigers. 240 square feet 1200- 136,000 sf

Leopards, Jaguars, Cougars 200 square feet 1200-6000 square feet

Lesser cats (Lynx, etc.) 72 square feet 1200-2400 square feet

Small cats (hybrid cats, etc.) 36 square feet. 1000 -2000 square feet

USDA only requires that the cage be large enough for the animal to stand up and turnaround in and a lot of states use the USDA standard rather than set standards of their own.

When you visit the zoo and see those magnificent million dollar enclosures, what you don't see are all the animals in tiny, off-exhibit cages. If animals must live in captivity, the least we can do is make them comfortable.

Cage Repairs and Renovations

With this many cages, there are always repairs and renovations to be made. The following was our most expensive renovation ever, as it was done underwater and requires stainless steel panels that cost over $200 each for sheets that were 4 feet by 8 feet. (we got a considerable discount)