SWCCF News 2025 08

Guigna and Puma threat reduction swings into action in and around Pumalin National Park, Chile

Jim Sanderson

Guigna and Puma roam Pumalin National Park and nearby forests surrounding rural villages in south-central Chile. But the threats to their continued existence are ubiquitous. Even within the national park, Guigna are at risk of diseases spread by feral dogs roaming freely under the umbrella provided by Chilean federal law. Yes, you read that correctly. Even park administrators and rangers are unable to remove feral dogs despite the threats posed to wildlife, especially Southern Pudu, Chile's miniature deer. As soon as Guigna and Puma leave the national park, they are at risk of even more threats such as tempting "free" food. Free-ranging chickens & loose livestock pose threats of retaliatory killing.

Moreover, because of its isolation, Pumalin National Park and Chaitén, the largest rural village, are difficult and expensive to reach. Nevertheless. Pumalin National Park is an important place for wildlife and for people that call Chaitén home. Led by Carlos Castro, the Colocolo Conservation Project, teamed with Pumalin National Park rangers, Rewilding Chile, and the Kiñewen Foundation to deliver pragmatic, practical conservation actions to Pumalin National Park and rural villages surrounding the park. Rural villagers living close to nature are about to learn that having Guigna and Puma is a treasure that deserves full protection.

Conserving Guigna and Puma in rural villages surrounding Pumalin National Park, Chile

Carlos Castro, Chile. Colocolo Conservation Project

In Chaitén, we are already working with all the surrounding schools in a joint effort with Pumalin National Park rangers and their community engagement program. Together with the Kiñewen Foundation and Rewildiing Chile, we are teaching children from local schools to use trail cameras to continuously monitor Guigna, Puma, and Southern Pudú outside Pumalin National Park.

Because the central park service administration employs a standardized monitoring program that allows trail cameras to be used just two months a year, we donated trail cameras to park rangers to enable continuous monitoring of Guigna and Puma within Pumalin National Park. Thus, the results of the monitoring programs can be compared to determine if our threat interventions are working to save Guigna and Puma from retaliatory killing for "stealing" chickens and sheep, respectively. All our actions and activities are made possible by our financial partners without whom nothing could be done.

To reduce known disease transmission from domestic pets to Guigna, our conservation actions also include free pet vaccination and sterilization programs in nearby communities. Displaying our logo and those of our partners, our attractive, informative signs inside Pumalin National Park explain why Guigna are important. We are active in all rural villages surrounding Pumalin National Park. Our goal is to have Guigna and Puma fully protected inside as well as outside Pumalin National Park, seamlessly coming and going just as they did long ago.

Our threat reduction interventions include building predator-proof henhouses and livestock corrals, pet vaccination and neutering to reduce disease transmission, community outreach and education programs that raise awareness and change behavior, and engaging children in our trail camera monitoring program. We aim to make the greater Pumalin area a model for all national parks to follow.

For the Colocolo Conservation Project team, working with rural people has been an incredibly rewarding, life-changing experience. It really is true that conservation is a social science. We improve the lives of rural people and they in turn help us protect the wild cats that fascinate us.

Colocolo Conservation Project

Chaitén, Chile

The difference between Wild cat and Wildcat

Jim Sanderson

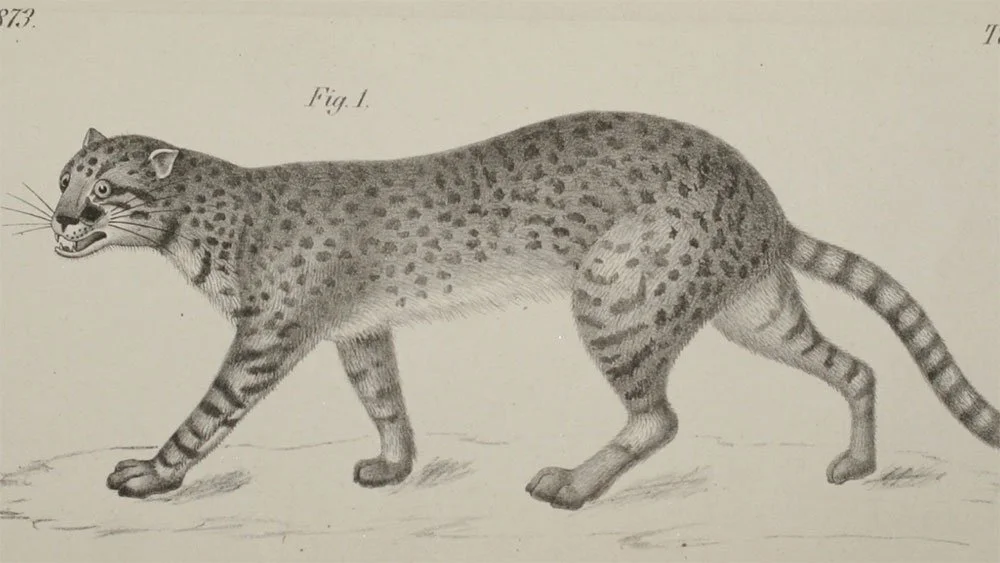

The word “wildcat” and the words “wild cat” are neither interchangeable nor equivalent. Simply stated, all wildcats are wild cats, but few wild cats are wildcats The illustration from 1896 depicts a European wildcat.

Recently I received an email from a colleague who wrote: African wild cat is awesome. Of course, I agree in principle, meaning I generally agree with this vague statement, but not necessarily in detail. What caused my hesitation?

If my colleague was referring to Felis lybica, and had written African wildcat is awesome, I would, without hesitation, agree. If my colleague had written: African wild cats are awesome, then I would also agree. But as stated, the sentence African wild cat is awesome is, at best, confusing.

Aficionados of the Felidae, the Great Family of Cats, should use the word “wildcat” and the term “wild cat” properly. The word wildcat refers to four species and included subspecies in the genus Felis: African wildcat (F. lybica), Asiatic wildcat (F. lybica (ornata)) (hopefully soon to be a unique species F. ornata), European wildcat (F. silvestris) and the Chinese steppe cat (F. bieti). In contrast, the term wild cat refers to any single species within the family Felidae with the sole exception of the domestic cat (F. catus). Thus, we could write that the wildcats are four species of wild cats, and the African wildcat is awesome.

When in doubt regarding usage, recall the title of Mel and Fiona Sunquist’s 452-page book Wild Cats of the World (Sunquist & Sunquist 2002). Had the title been Wildcats of the World, considerably fewer pages would have been used. A quick look at the Table of Contents shows the domestic cat chapter was included in the section titled Wildcats along with the European wildcat and African-Asian wildcat. While considering the domestic cat as a wild cat might be questionable, there is little doubt the choice simplified the title.

To us, all cats are indeed awesome! Hope this helps.

Fishing Cat Guardian Clubs: Slowly Embracing Conservation

Ganesh Puri, Nepal, Western Terai Fishing Cat Conservation Project

Since 2021, we’ve been working with local youth through the Buddhabhumi Fishing Cat Guardian Club in Kapilvastu. Today, under their own leadership, the club successfully organized an inter-school painting competition focused on Fishing cat conservation. Twenty students from ten nearby schools were invited to participate. Alongside the competition, they shared important messages about the Fishing cat, what it is, the threats it faces, why it matters, and why we must protect Fishing cats. Prizes were awarded for the best conservation-themed artwork with a strong message.

As Jaganath Tharu, leader of the Guardian Club, said: “The 20 participants didn’t just draw the Fishing cat on paper, they took the message of its conservation to heart.” With support from the Western Terai Fishing Cat Conservation Project, we were able to make the event happen. We’re feeling more motivated than ever, and we’re committed to ensuring the Fishing cat doesn’t disappear from our region.

JGS: Ganesh (fourth from the right in the above photograph) is far too modest. His numerous community conservation projects are winning fans not just in Nepal, but in other countries as well. Ganesh is now an invited speaker at conservation symposia. You’ve come a long way, Ganesh. Your efforts have made an outsized difference for rural communities, children, and Fishing cats. Congratulations.

Rusty-spotted cats traffic signs change behavior

Mitra Pandy, Nepal, Rusty-Spotted Cat Working Group

Roadkill is a major threat to the Rusty-spotted cat in India and Nepal, particularly in areas where roads intersect their natural habitat. Expanding networks of highways and forest-side roads continue to grow. In the Rusty-spotted cat habitat of Nepal alone, side roads have a daily minimum of 80 to 100 four-wheelers and average 175 motorbikes, while highways allow at least 550 four-wheelers and 700 motorbikes daily.

To mitigate roadkill, in July 2024 we began the installation of road signs with the message “Drive Slow: Rusty Spotted Cat Habitat.” These signs were strategically placed in areas known to be Rusty-spotted cat crossings and previous roadkill incidents. In Nepal, 15 signs were installed at key locations in Bardia and Kanchanpur districts. These included the East-West National Highway near the Amreni Army Check Post, Bathanpur-Madhela Community Forest, Chitkaiya Community Forest and Thakurdwara Community Forest. Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh state of India, 27 signs were installed along critical stretches of highways between Puranpur to Khatima, Mailani to Bhira, Palia to Gauriphanta and Gola to Khutar. Three of the signs installed along the highway within the Rusty-spotted cat habitat in India were found damaged by a herd of elephants (see picture below)

We monitored the impact of our signs. In India, a three-week follow-up survey was conducted to assess driver behavior and the effectiveness of our signs. Observations revealed that approximately 90 percent of drivers, including those operating auto-rickshaws and four-wheelers noticed the signs and significantly reduced their speed while passing through the marked areas. Additionally, local forest officials were engaged to assist in ongoing monitoring, including tracking vehicle speeds and wildlife movement near the roads. In Nepal, although formal surveys were not conducted during the initial phase, informal observations and local feedback indicated a noticeable increase in driver awareness and caution along the highways and adjoining forest roads. The presence of the signs sparked curiosity among both local residents and travelers, further increasing awareness about the presence of the Rusty-spotted cat in the region.

Since the installation of our signs in both countries, no roadkill incidents of Rusty-spotted cats have been recorded in the targeted areas. The visible change in driver behavior and the absence of new roadkill reports suggest that our signs made a positive difference. Nevertheless, we realize that more than traffic signs are needed so our team is hard at work implementing other threat mitigation actions.

JGS: Note the cross-border cooperation within the Rusty-Spotted Cat Working Group. The impact of signs is often indirect. For instance, local forest officials likely never heard of Rusty-spotted cats or did not know the cats were present. Also, the sins give rise to selfies that create even more awareness. I want one. A special call-out to Mitra for monitoring the impact of the threat mitigation interventions.

Rusty-Spotted Cat Working Group

Elephants don't follow traffic rules in Nepal or India

If they did, they would walk facing the left side of the road and read the sign.

Protecting chickens and Pampas cats in rural Peru

Zoila Vega Guarderas, Peru, Pampas Cat Working Group

In 2022, at the invitation of Adrián Ricalde, a local conservation leader, we visited San Felipe, a rural community in northern Peru. Adrian informed us that dogs had killed a Pampas cat that entered a chicken coop. In rural villages, the loss of chickens causes economic hardship and resentment. The result is inevitable and never favorable for Pampas cats. Alarmingly, all 60 families interviewed had killed at least one Pampas cat in the past three years.

While initial skepticism of our offer to help was also alarmingly high, we began working with 19 families that believed in our project. At our expense, we supplied the necessary materials to build predator-proof hen-houses, then provided farm-raised chickens (that are accustomed to hen-houses), distributed veterinary kits, held chick vaccination clinics and provided workshops on poultry health. Our success motivated additional families to enlist in our project. Over three years, we've enabled construction or repair of 176 hen-houses, distributed 880 chickens, vaccinated more than 1000 chicks, sponsored 10 workshops, and donated five veterinary kits.

Families now have safe chickens, fresh eggs, and have experienced no losses to predators. Most importantly, none of these 176 families have killed a Pampas cat or any other carnivores. Through our workshops, they now understand the ecological importance of the Pampas cat, and predation losses have dropped to zero. The community has shifted from viewing wild cats as a threat to living in harmony with nature. Moreover, they realize there is no need for so many dogs.

One major challenge was overcoming the community's initial resistance. Many doubted the project would work. Hen-house designs had to be adapted to local customs and conditions, and community workshops helped build trust. A turning point came when local resident Doña Rosa, once skeptical, shared that she had experienced no losses for six months. Her success went viral and convinced others.

Our project demonstrates that with empathy and practical, pragmatic solutions, humans and wild cats can coexist. Chickens and Pampas cats can simultaneously be protected. We strengthened community bonds and increased environmental awareness. San Felipe now stands as a model for community-led conservation. Our project is both scalable and sustainable because the local people now know what to do. With the help of Adrián Ricalde and Doña Rosa who do the talking, we are reaching out to other rural communities.

We thank our financial partners and the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund for supporting our project.

JGS: Zoila is a people-person. I've watched Zoila in action. She does not tell people how to predator-proof their hen-houses. After all, no two hen-houses on earth are the same. Instead, Zoila shows them a video of a Geoffroy's cat climbing a hen-house door, entering over the top, securing a hen, and safely escaping. Three times! The person watches the video, laughs, then points to possible entryways into their hen-house. The project supplies all necessary materials for the person to repair their hen-house. Following an inspection, rewards are given and a new team member is vested. Zoila makes it look easy.

Three Brazilian Pampas cat siblings in dire conditions

Jim Sanderson

With several Brazilian colleagues, I returned to a small but wonderful zoo, Jardim Botânico e Zoológico Municipal Cachoeira do Sul, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. We visited to see three Pampas cats (Leopardus braccatus) quite literally dumped at the zoo. We previously supplied the materials to build a large enclosure for small cats and could do so again but there is a lack of ground space.

We were shocked to see the three siblings housed in a container-like structure with no operable windows, a tile floor, no fresh air or sun, and no ventilation. They have neither felt soil nor sun for more than a year. I must add that the zoo staff has given them the best care possible notwithstanding their miserable living quarters.

I personally have only seen once previously what might be commonly called the Black-footed Pampas cat or the Savanna Pampas cat since the habitat is Savanna grasslands, They do not occur in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. I was thrilled to be up close and personal taking as many pictures and videos as I could get while my colleagues recorded the two siblings in another bathroom-like enclosure.

The zoo director, whom we have known and worked with for several years, informed us that he was told by a federal agency that the siblings would be relocated to another zoo pending authorization that has not yet arrived. If we had our own rescue and rehabilitation center in Brazil, we would take them at our own expense.

In cooperation with the zoo, we are doing everything we possibly can, pleading their case, giving them a voice, sending pictures, seeking help from government. No small cats left behind. See more pictures below.