Private Ownership Ends Badly for Wild Cats

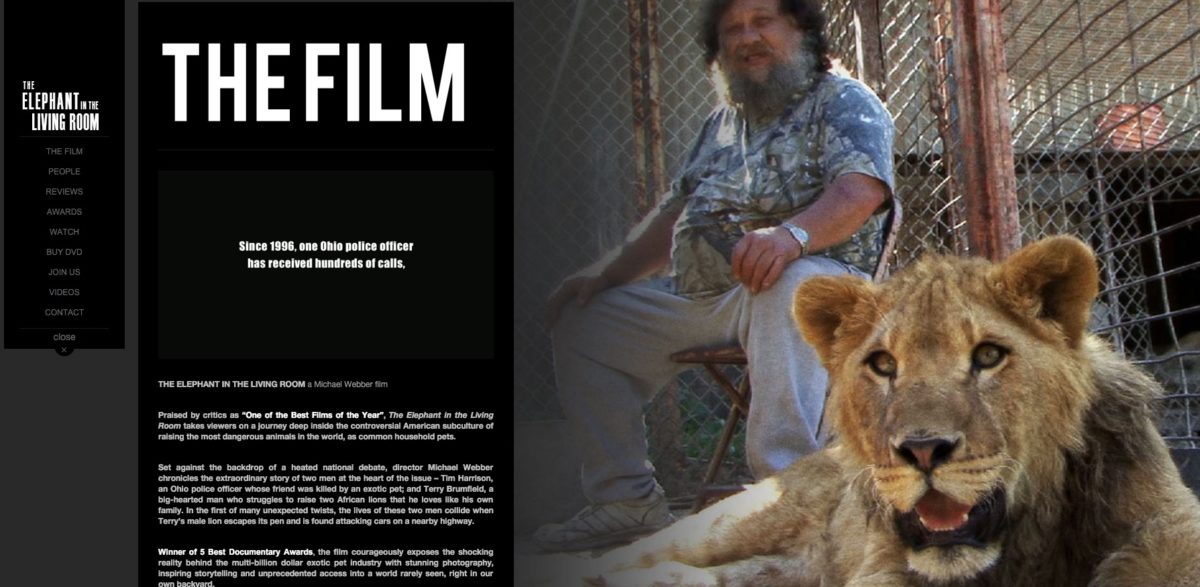

Here’s the most telling quote from the new documentary, The Elephant in the Living Room, about the practice of keeping large, wild animals as pets:

“I don’t have any happy endings,” said Tim Harrison, a public safety officer who specializes in rescuing escaped and mistreated animals. “No happy endings at all with big cats.”

The movie’s apparently not very discriminating publicist offered to send me an advance DVD of Elephant, which opened Friday in several cities and is scheduled to open at the Regal Citrus Park 20 theater in Tampa on April 15.

Though, obviously, I’m not a film critic, I took him up on it because I figured to see a lot of Florida.

Released Burmese pythons, after all, are reordering the food chain in our most famous natural landmark, the Everglades. I live within 15 miles of at least four people who raise large cats. And one of the most widely known residents of Hernando County — Jim Jablon — got that way by spending January in a cage with two young lions.

Where else but Florida could you find this kind of craziness?

Well, according to Elephant, all over the United States, where about 15,000 lions, tigers and other big cats are kept in captivity — only a tiny percentage of them in zoos or licensed sanctuaries.

Personally, the most disorienting scene showed Harrison stalking an escaped mountain lion in woods maybe 10 miles from my childhood home in normal, boring old southern Ohio. When I was a kid, seeing a fox was a big deal.

But, restoring my faith in Florida’s weirdness, the state does, at least, lead the country in big cat maulings and escapes, said Carole Baskin, CEO of Big Cat Rescue in Tampa.

And really, she said, the large captive population of wild animals is something I shouldn’t be joking about, with Jablon being a perfect case in point.

The video feed of his stay in the cage, which was picked up by media outlets as far away as England, shows him playing with the adolescent lions, patting their stomachs, kissing them and generally reinforcing the message that these ferocious creatures can be treated as pets.

Worse, he is trying to breed them.

Because sanctuaries have room for only a tiny number of unwanted large wild animals, the more that are born, the more that will come to a very unhappy end — euthanization.

Worst of all, the cats Jablon hopes to breed are white lions.

Have you ever ohhed and ahhed over white tigers at zoos or attractions such as Busch Gardens? Well, you shouldn’t. That white coat is a genetic rarity which, even in the wild, may be the result of inbreeding. The easiest way to produce more white tigers in captivity is definitely more inbreeding, which is why this population is rife with serious birth defects such as crossed eyes and cleft palates.

Tilson doesn’t have any proof the same thing has happened yet with white lions, though it will if people like Jablon create an audience for them as cuddly novelties, especially because of their lack of genetic diversity: all the world’s captive white lions are descended from the tiny wild population found in the Timbavati Game Preserve in South Africa.

In any case, Jablon’s contention that he is trying to breed them to perpetuate an endangered variety has zero validity. They are not a distinct, biologically viable species or subspecies, Tilson said; there is absolutely no ecological justification to breed animals for light-colored coats.

Jablon says his white lions came from a buyer who lives in Ocala and remains a part-owner. But beyond that, he knows little about them, can’t even say for sure the male and female are not related. And when a U.S. Department of Agriculture inspector showed up at Jablon’s home-based, 14-acre operation just north of County Line Road when the lions were being delivered, Jablon couldn’t produce documents demonstrating how he’d acquired them.

Among the other violations inspectors found on this and other visits last year: enclosures with fences too short or poorly designed to contain big cats, their care left to untrained assistants and dangerous techniques used to handle the lions.

Most of these problems have since been fixed, Jablon said, and the ones that haven’t are due to what he called the changing, unreasonable demands of inspectors.

Okay, but I offer this opinion, just because Jablon said he managed to raise $75,000 with his stunt and, knowing him, will likely try something similar again: I wouldn’t give him a nickel.

And this is not just because Jablon has veered off his original, relatively noble track of rescuing injured bobcats and deer and nursing them back to health.

It’s because all the money and effort that goes into feeding and sheltering these animals barely makes a dent in a problem that, ultimately, only the preservation of habitat can fix.

Big Cat, for example, has turned down as many as 500 animals per year in the past decade (though far fewer recently, because of increased trade regulations) while housing only 114.

True, Baskin doesn’t breed her cats, which is a big distinction. But it seems to me that if this sanctuary’s only goal was to rescue animals it would house more of the most commonly disposed-of breeds — including lions and tigers — and fewer curiosities such as servals and ocelots.

A collection with a nice, wide variety, of course, helps draw visitors and sell gifts, which are big reasons Big Cat’s total revenues in 2009 were $1.7 million. This is another issue with the people who claim to have only the pure motive of saving animals. You don’t have to look too hard before the impurities start to show up. (see note at end of article)

Harrison is the hero of Elephant, which tracks his crusade to outlaw the keeping of dangerous exotic animals as pets. Besides coming off as an shameless publicity hound, he is also shown, well, treating dangerous animals as pets — stroking the paw of a lion and the belly of a cougar.

Then there’s the Colorado sanctuary held out in the movie as a model in the film, a place where Harrison says a lion can “be a lion.” But in 2006, due to a slump in donations, the owner threatened to euthanize all 155 of his animals, including wolves, bears, tigers and lions.

Happy, happy, happy.

By Dan DeWitt, Times Columnist

In Print: Sunday, April 3, 2011

I agree that there are no happy endings but am dismayed that Dan DeWitt took such a pot shot at us when I had sent facts in writing, that were not included in his portrayal of us, which explains why we cannot take in more lions and tigers.

“We are saving hundreds, if not thousands of big cats each year because of the work we are doing to end the trade in them. The email before stated the steep incline in the number of cats in need of sanctuary each year and the steep decline as soon as we were successful, along with help from the Humane Society of the United States and other major animal protection groups, in getting better federal legislation and state bans in place.” I sent a chart that shows the cats we had to turn away and the cats we have taken in.

“Our last meat shipment came with the announcement that it is going from 1.10 lb to 3.10 lb which is going to triple our feeding budget going forward. We feed Natural Balance because it has kept our cats far healthier than any other option, thus the long lives. Just the direct cost of rescuing a lion or a tiger was about 5,000 a year, without overhead but will now be closer to 10,000 a year. Nothing hurts more than turning away a big cat, but I am doing a huge disservice to the cats we have and the hundreds or thousands in need of rescue if I take on more than I can care for or if I decide to make the fundraising treadmill turn faster when I should have been ending the problem at its root.”

“Our Acquisition Policy is online and I can send it if you like, but essentially we do not allow Keepers to clean or feed Class I animals, like lions, tigers or leopards, until they have put in 2 years with us working with the smaller cats. We do not allow any contact here, but even so feel it takes 2 years of working with the lesser cats to insure safety working around the great cats. One of the biggest factors in deciding on a rescue is, “Do I have the appropriate number of trained staff and volunteers available to provide the daily care for another Class I cat?” We always offer to take in the smaller cats, because we have the manpower, but it is much more of a challenge for the bigger cats. Another big factor in our acquisition policy is that we require the owner to give up their right to ever own a big cat again. Most are just looking for a place to unload their adults so they can breed or buy more cubs for profiteering. If they won’t agree to that term, we won’t take their cat. To do so just perpetuates the cycle of abuse.”

“We can’t rescue our way out of this big cat crises in America. The only thing that has proven to work is to ban the private possession of dangerous wild animals. In 2003 we had to turn away 312 big cats due to lack of space and funds and every other year that number was doubling. In Dec. 2003 the Captive Wildlife Safety Act, a federal bill that made it illegal to sell a big cat, across state lines as a pet, passed. The next year, instead of having to turn away 500-600 big cats we “only” had to turn away 110. As 8 more states have passed bans we have seen than number continue to drop. In 2009 it dropped to 50. It went up in 2010 to 89 but that was because of 23 lions at a circus and a huge sanctuary that both shuttered.”

How to tell the good guys from the bad guys?

Readers should ask themselves:

1. Are they adding to the problem by breeding, buying, selling, trading or through actions that make others want to pet cubs and perpetuate the abuse?

2. What are they doing to end the problem? Big Cat Rescue spends more than $25,000 per year to provide CatLaws.com which enables visitors to see all of the big cat abuse issues that are currently happening and puts them in touch with the decision makers to end it.

3. Are they behaving in a responsible way that insures lifetime care for the animals they rescue? Our 990s and Audited Financial Statements are available at Guidestar.org and we have the highest charity rating given by Charity Navigator. We have an endowment set up at the Community Foundation of Tampabay so that if another 911 hits our cats will be able to ride out the financial crisis.