Black-footed Cat Working Group

The Tiny Titan of the Savannah: Why Africa’s Deadliest Cat Lives in a Borrowed Basement

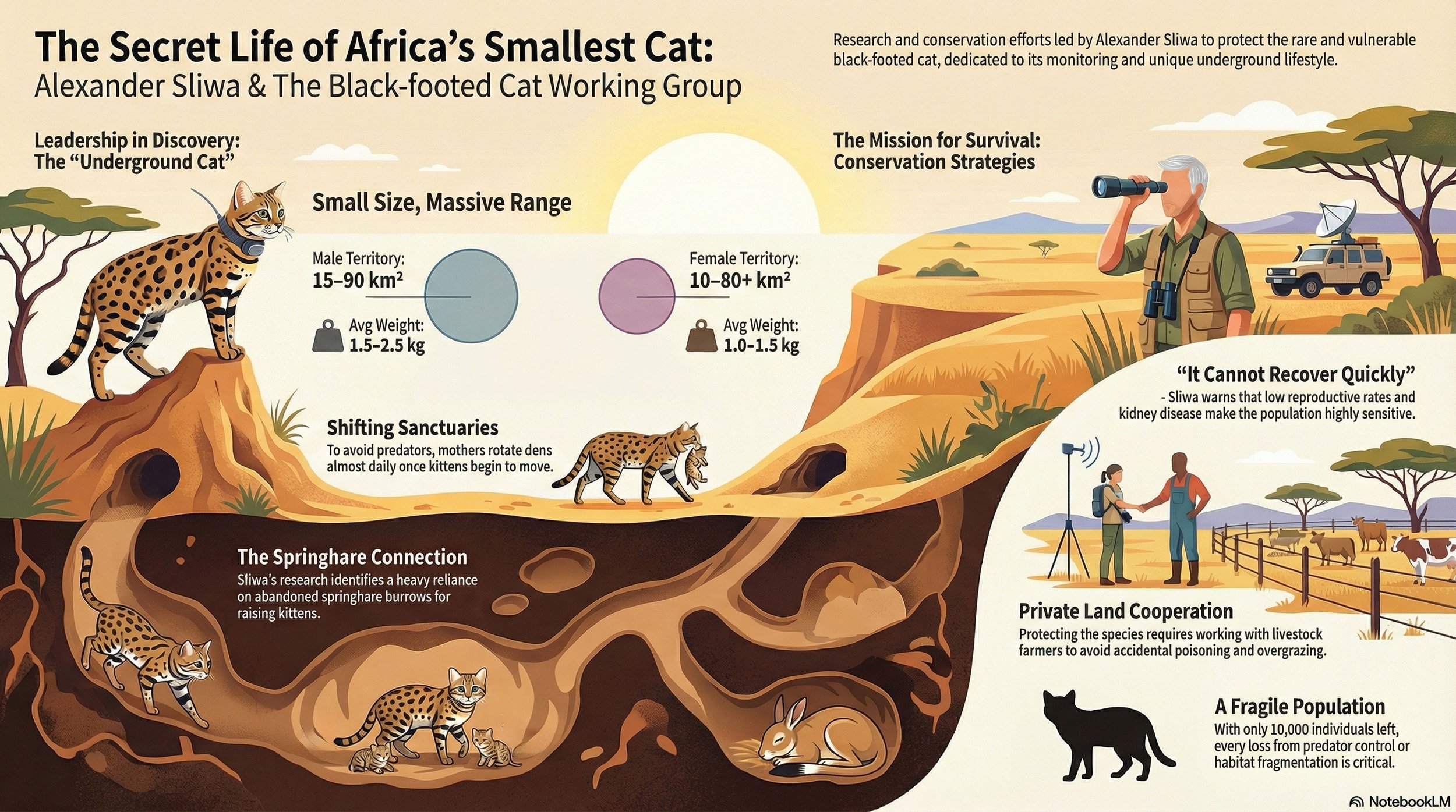

In the vast, semiarid stretches of Southern Africa, a shadow moves through the scrub with a lethal precision that puts the "Big Five" to shame. It is barely a third the size of a domestic tabby, weighing between 1 and 2.5 kilograms (2.2 to 5.5 pounds). To a casual observer, the black-footed cat (Felis nigripes) looks like a fragile, pint-sized pet. In reality, it is the most efficient feline predator on Earth.

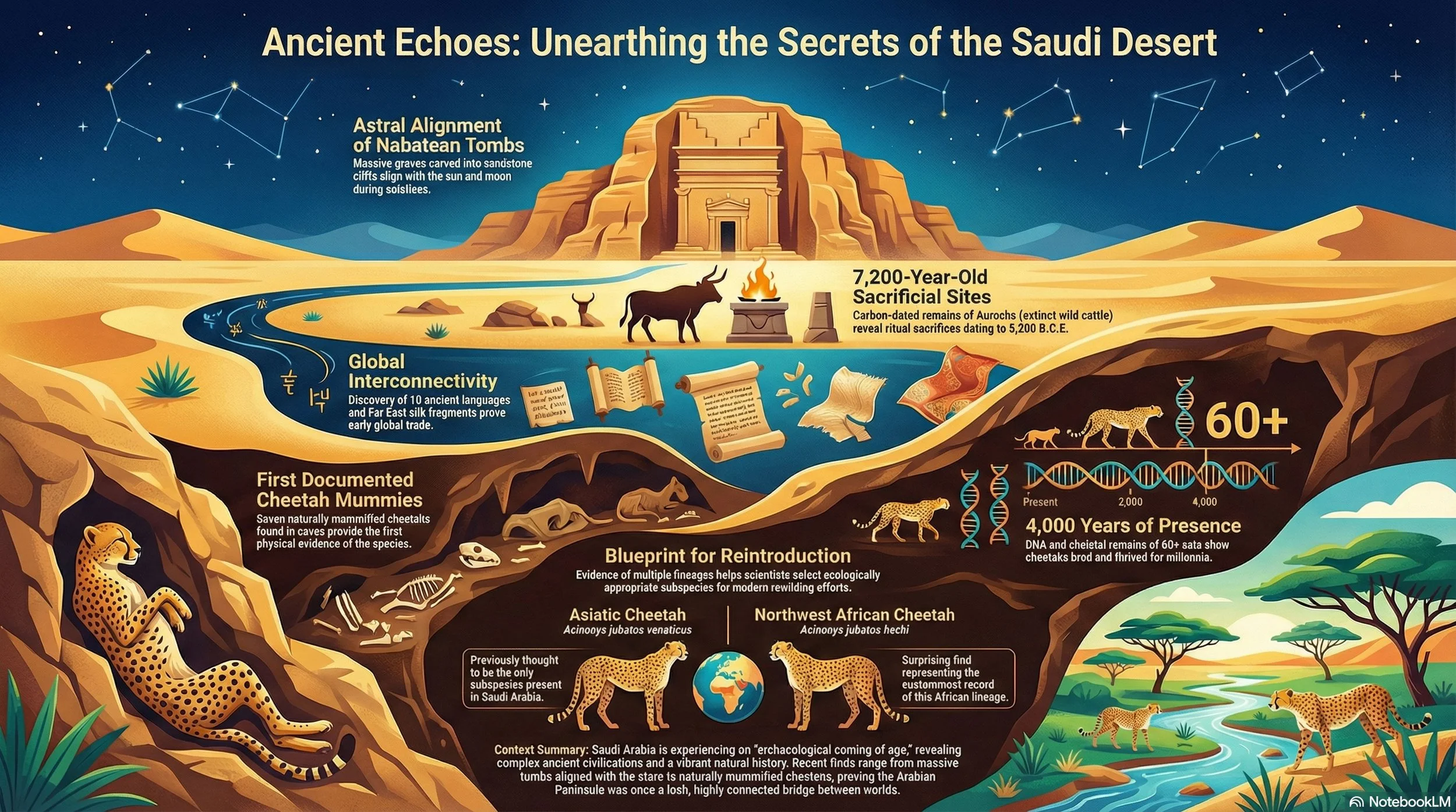

For years, this elusive species—whose total population hovers at a precarious 10,000 individuals—has been the focus of Dr. Alexander Sliwa and the Black-footed Cat Working Group. As the primary authorities on the species, these researchers have spent decades investigating a fundamental ethological puzzle: How does a one-kilogram carnivore with high caloric needs and a long list of larger predators manage to thrive in such a punishing landscape? The answer was eventually decoded beneath the soil. To survive the heat and the hunters of the savannah, this tiny titan has adopted a surprising strategy: it has become a master of the "borrowed basement."

1. The Most Efficient Hunter You’ve Never Heard Of

While lions and leopards command the headlines, the black-footed cat quietly outperforms them both. These cats are remarkably active, covering vast territories that seem impossible for their leg length. Females patrol ranges from 10 to more than 80 square kilometers, while males roam even larger expanses, between 15 and 90 square kilometers. They are "high-energy" specialists, hunting small rodents, birds, and insects throughout the night with a success rate of roughly 60%—triple that of a lion.

This lifestyle is an evolutionary marvel. Sustaining such an intense metabolic fire in a tiny body requires near-constant hunting. However, this high-octane pace creates a biological dilemma: how to recover that energy without being eaten or cooked by the African sun. The cat's nocturnal, subterranean lifestyle is the essential "off-switch," providing the thermal regulation needed to conserve energy for the next night’s marathon.

"It’s really small, but very active and unique in its nocturnal behavior," says Dr. Alexander Sliwa. He notes that while they are tiny, they are "beautiful, like miniature leopards."

2. An Unusual Architectural Dependency

Survival for the black-footed cat isn't just about what it eats; it's about the "cat-and-mouse" irony of its housing. While the cats are prolific hunters of small rodents, they have a specific, non-predatory relationship with the springhare (Pedetes capensis). This large rodent—resembling a cross between a kangaroo and a rabbit—is too large for the cat's menu, but its engineering is essential for the cat's survival.

As researcher Harold Brindley puts it: "This is just another way cats depend on rodents — first for food, and now for shelter!"

A Constantly Renewed Network of Refuges Because springhares frequently dig and then abandon their burrows, they create a vast, underground infrastructure across the savannah. These tunnels provide the black-footed cat with a "constantly renewed network" of housing. This subterranean world acts as a critical thermal buffer and a fortress against larger predators like jackals and caracals. Interestingly, there is a gendered nuance to this dependency: while females rely almost exclusively on springhare burrows, males are more opportunistic, occasionally utilizing larger holes excavated by aardvarks or porcupines.

3. The Nomadic Strategy of Motherhood

Research led by Brindley and Sliwa has illuminated the complex way female cats manage their dens. Unlike many felines that remain stationary to protect their young, the black-footed cat is a nomad by necessity.

The research indicates that females use an average of 12 different shelters per month within their territory. This "moving house" strategy becomes a frantic race once the kittens reach six weeks of age. As the young begin exploring, the mother often changes their location almost daily to prevent the buildup of scent trails that could lead a caracal or jackal to the den.

"I can make the obvious assumption that predation risk is high when those little furballs first start exploring the world and playing with everything while mom is trying to hunt and keep them safe," Brindley explains.

This constant movement is a brilliant evolutionary trade-off. By treating the landscape like a shifting chessboard of springhare burrows, the mother minimizes exposure in a world where the odds of reaching adulthood are razor-thin.

4. A Population on a Knife’s Edge

Despite its hunting prowess, the black-footed cat is incredibly vulnerable. They have a low reproductive rate, producing at most two kittens a year, which means the population of 10,000 cannot recover quickly from sudden losses. Furthermore, the species is genetically susceptible to AA amyloidosis—a devastating kidney disease caused by abnormal protein deposits that weakens individuals and leaves them easy prey.

The cat also faces significant indirect human-wildlife conflict. According to Sliwa, the threat is rarely intentional; farmers aren't hunting these cats, but they are hunting jackals. Poisoning and shooting aimed at larger livestock predators often claim the black-footed cat as collateral damage. Additionally, overgrazing by livestock can drive away the springhares, effectively destroying the "housing market" the cats require for reproduction.

Sliwa emphasizes that protecting the cat requires protecting "working landscapes." Conservation isn't just about fences; it’s about the cooperation of the farmers who manage the land, ensuring that the ecosystems—and the burrow-digging rodents within them—remain intact.

5. The "Love at First Sight" Conservation Factor

The greatest challenge in protecting the black-footed cat may be its invisibility. Martina Küsters, coordinator of the Black-footed Cat Research Project Namibia, points out that it is difficult for the public to value a species they never see. However, she believes the cat’s "feisty" personality has a unique power to inspire.

“If you ever see one, you fall in love," Küsters says. "They’re tiny, full of character, and very unique. They’re beautiful, like miniature leopards. When we talk about unique biodiversity, this is a perfect example.”

In modern conservation, this emotional connection is a vital tool. By framing the cat as a "miniature leopard" with the heart of a lion, researchers hope to turn it into a flagship species for the protection of the entire Southern African savannah ecosystem.

Conclusion: A Landscape of Hidden Connections

The survival of Africa’s smallest cat is not a solo act; it is a delicate dance of interdependency. Its life is tied to the industrious springhare and the land-management choices of local farmers. If the burrows disappear, the cats disappear. If the working landscapes are managed without regard for the small and the hidden, the "Tiny Titan" of the savannah may vanish before we truly understand the depth of its secret life.

As we look closer at the relationship between this feline and its rodent architects, it raises a compelling question: how many other hidden interdependencies are currently sustaining the natural world, waiting to be discovered before they are lost forever?

Note: Dr. Alexander Sliwa asked that we be sure to give a shout out to his fellow fighters for black-footed cat recognition and admiration; Beryl Wilson, Martina Küsters, Hal Brindley, and Dr. Jim Sanderson. Alex also wants viewers to know that “the legs and tail of the AI generated black-footed cats are a bit too long, so the cats look more like leopard cats in shape than black-footed cats. The tail is only 40% of the head-body length in the species.” This small cat is so elusive and photos and videos so rare, that AI has not had the opportunity to really capture the exact look, but we will update our content as that improves.

Please note that all of the images were created by AI and are not exactly representative of the cats depicted. For actual photos and videos visit:

https://www.blackfootedcat.com/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/black.footed.cat

https://www.instagram.com/blackfootedcat.life/

For the research paper visit: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385040971_The_underground_cat_burrow_use_by_female_black-_footed_cats_Felis_nigripes